On Dec. 5, Lilly Endowment shared news of $48 million in grants for 17 projects as part of its Strengthening Indianapolis Through Arts and Cultural Innovation initiative. Designed to “encourage community building and celebrate creativity,” this one-time competitive grant program supports a broad swath of projects and initiatives across the city — including $3 million toward Big Car Collaborative’s ongoing efforts to support its home block just south of Garfield Park on the near southside.

Big Car co-founder and executive director Jim Walker explains the project this way: “Cruft Street Commons is a collaborative effort to develop a socially cohesive, culturally focused city block where artists and other leaders work together to support stronger communities across Indianapolis. We’ll bring people together to build social cohesion and address civic and community challenges in our city.”

The $3 million will make it possible for Big Car to work in partnership with Central Indiana Community Foundation and several others to:

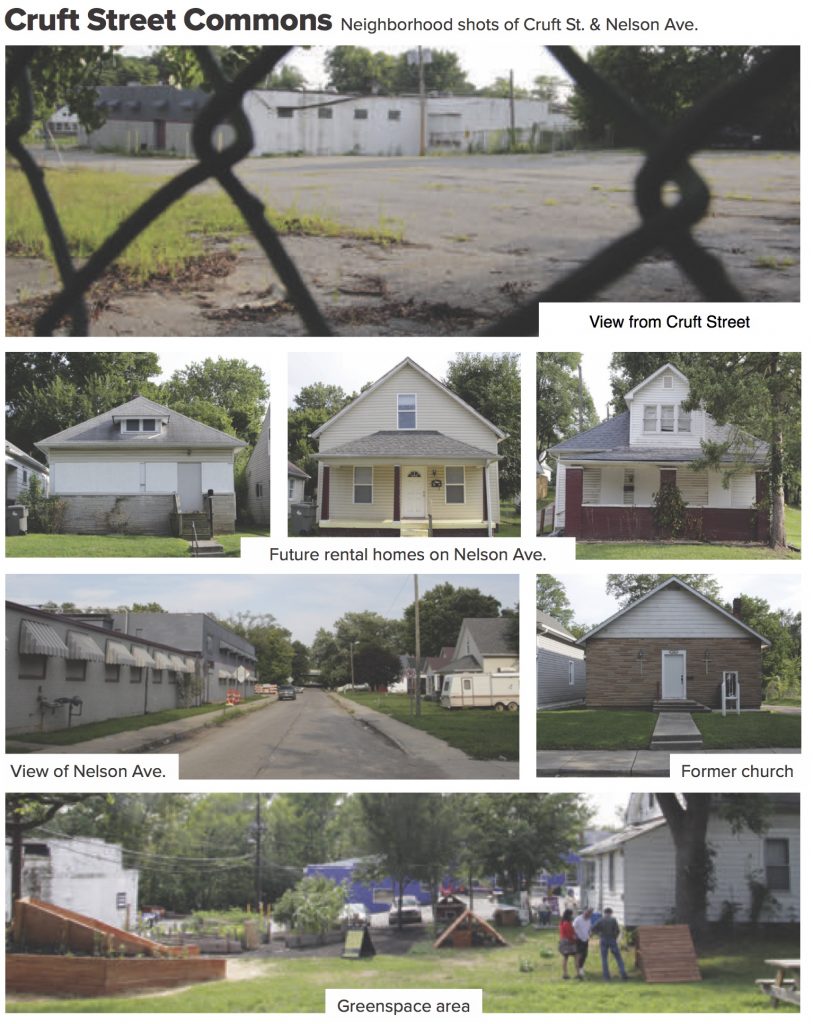

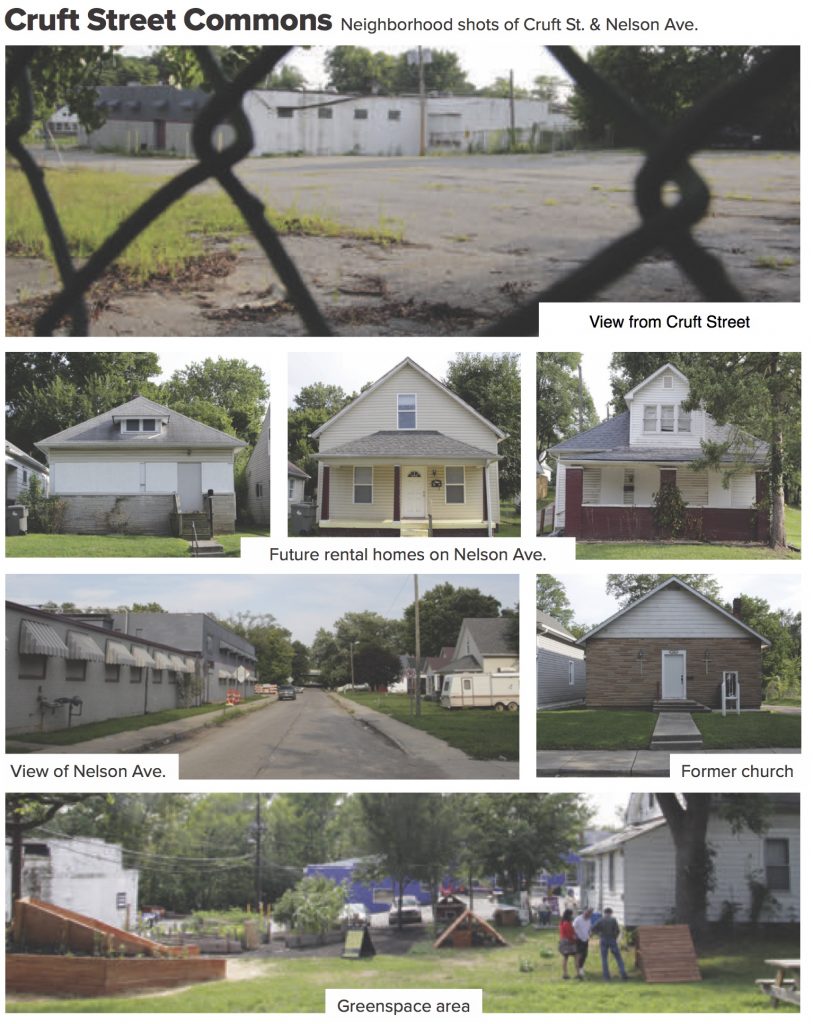

- Renovate four vacant houses as affordable rentals for artists (three on Nelson Ave. and one on Cruft Street)

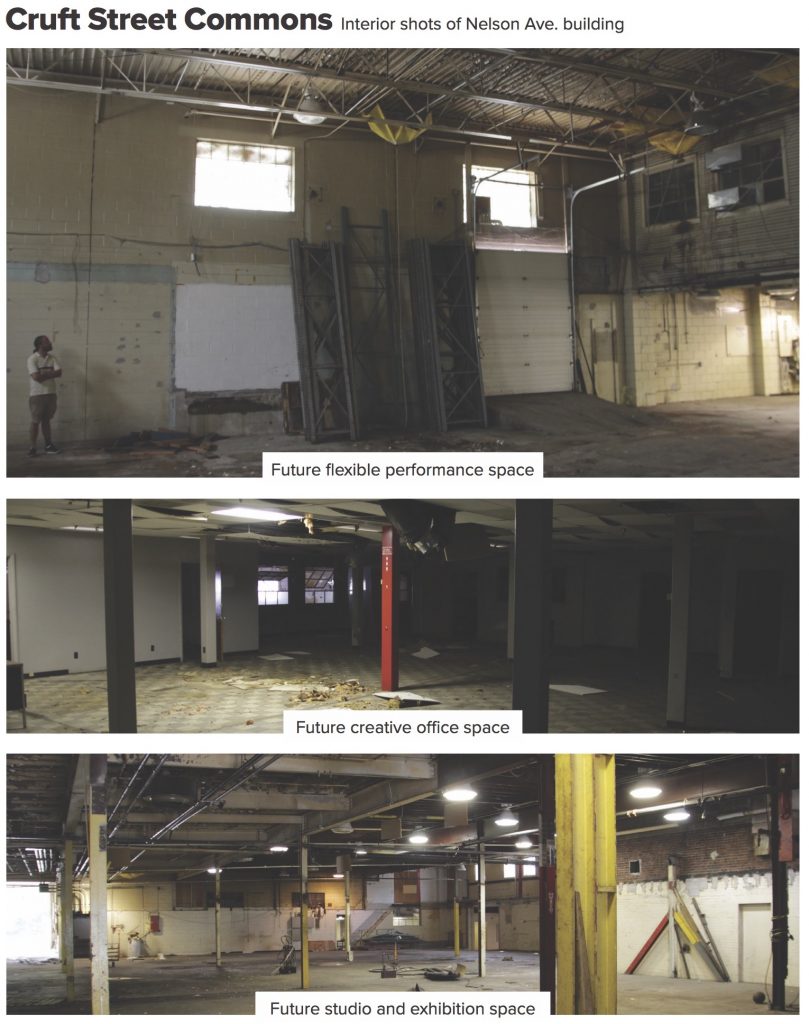

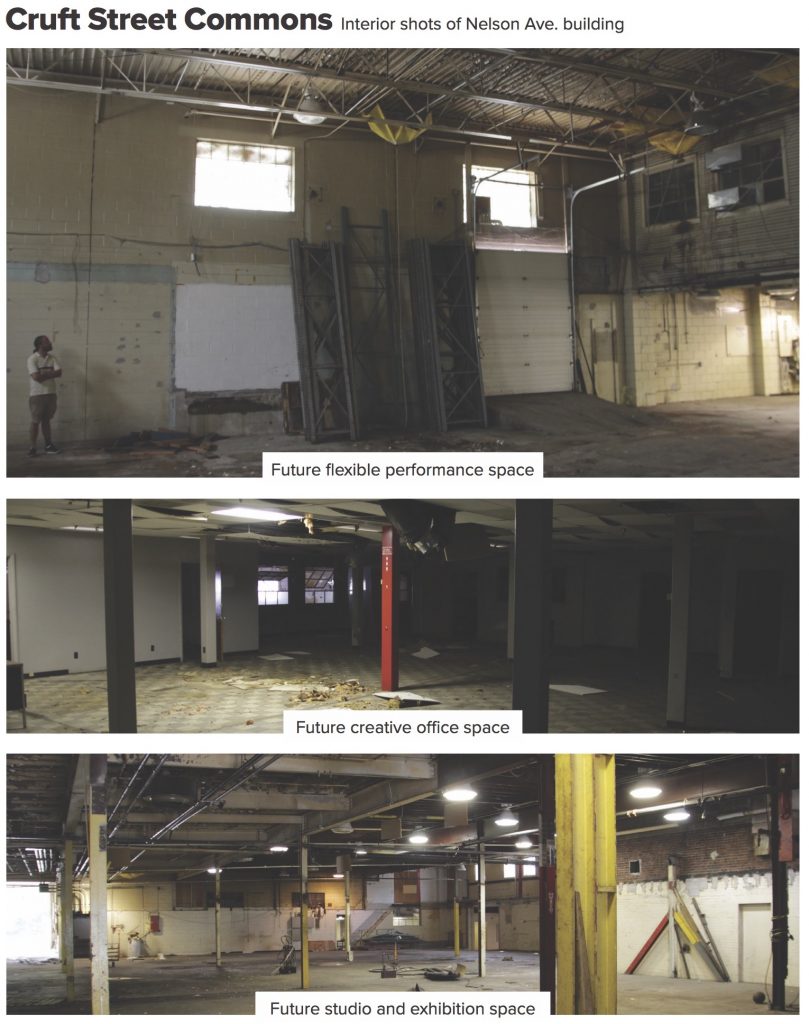

- Repurpose a vacant 46,000 square-foot former factory behind Tube Factory artspace for studios, exhibition space, performances, and other public programming

- Complete a public gathering area in the greenspace between Big Car artist housing on Cruft Street, Tube Factory, and the large building to be renovated

- Work with partners including South Indianapolis Quality of Life and The Learning Tree to support social cohesion in neighborhoods through social art strategies

- Team up with Indiana University Public Policy Institute (IU PPI) on data tracking, evaluation, real-time feedback, and short and long-term strategy

- Document the project and community impact with, video, photos, and stories that will be shared online and Big Car’s communityradio station, WQRT, along the way.

Other partners on the project include: Garfield Park Neighbors Association, Bean Creek Neighborhood Association, Indianapolis Neighborhood Housing Partnership (INHP), Riley Area Development, University of Indianapolis, Solful Gardens, the City of Indianapolis, Rundell Ernstberger, Deylen Realty, Blackline Studio, and Pattern.

More about Cruft Street Commons

As the project develops this group of artists and leaders working and living in this micro community will focus on supporting this currently challenged block located in the Garfield Park neighborhood, the near southside, and neighborhoods around Indianapolis. This ongoing and consistent work will focus on inclusive, informal arts practices that share the joy of creative expression in engaging ways, bring citizens together, and boost quality of life for people of all ages and backgrounds.

Cruft Street Commons builds on $2 million-plus in public and private investment already on the block at Tube Factory (home of a community gathering and exhibition space and workshop), sound art gallery Listen Hear (home of Big Car’s FCC-licensed FM radio station, WQRT), and the fully funded affordable homeownership program on Cruft Street in partnership with Riley and INHP.

With this next phase, Big Car teams up with experienced and dedicated partners to create a socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable micro-community that supports equitable, collaborative, and positive macro-level change throughout the city. This plan is what Australian scientist Bill Mollison would call “social permaculture” and what sociologist Eric Klinenberg calls “social infrastructure.”

Big Car, an artist-led organization founded in 2004, is saving and repurposing visible structures — buildings and outdoor gathering spaces — to develop equitable and inclusive social infrastructure.

Walker, co-founder Shauta Marsh, and multiple other members of the Big Car staff are artists and curators who also live in the neighborhood on the near southeast side of Indianapolis.

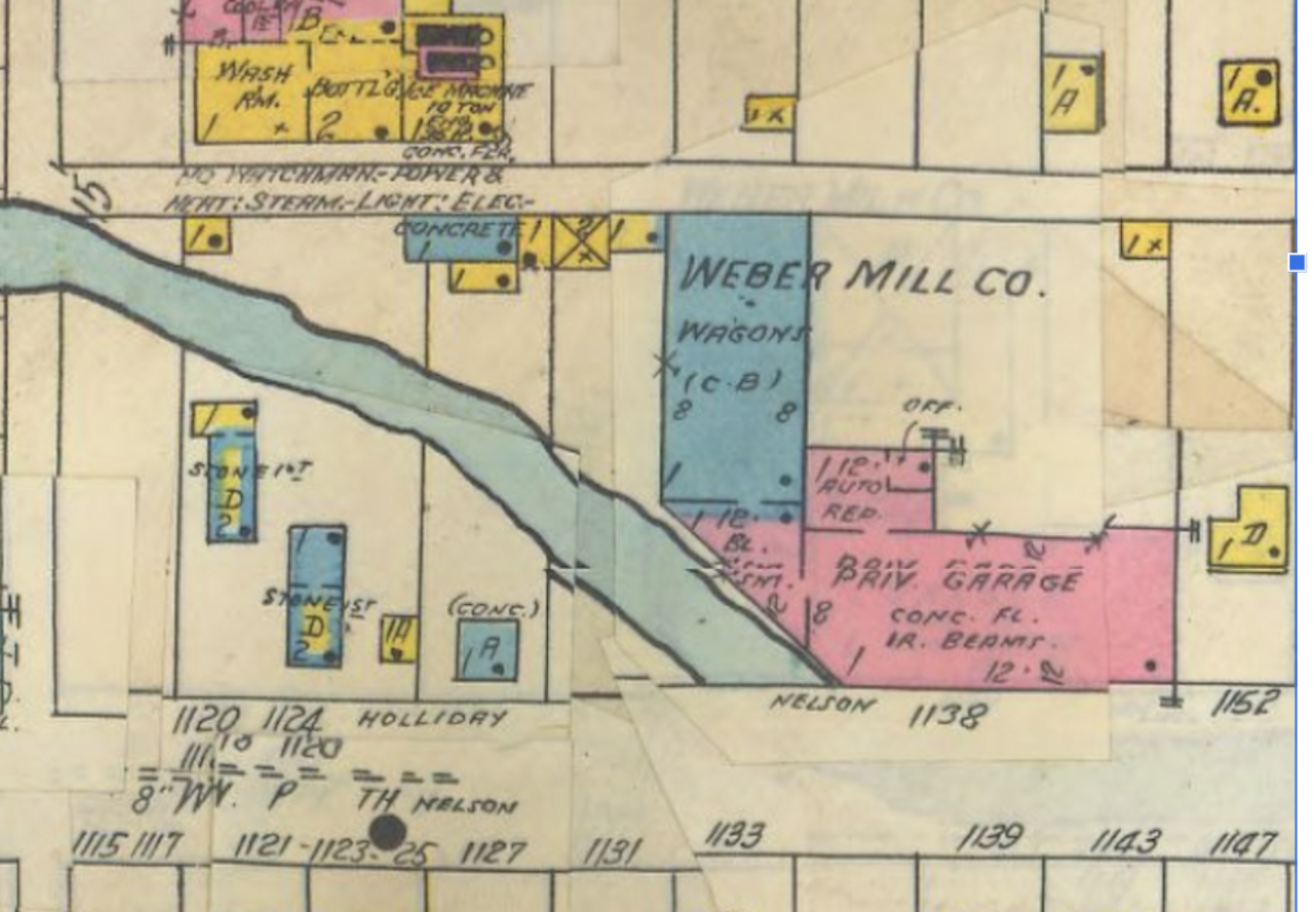

Cruft Street Commons is located less than a block away from Garfield Park, a new Red Line station and an existing BlueIndy electric car share hub. Its location offers a bike-friendly route to the Indianapolis Cultural Trail in Fountain Square via Pleasant Run trail 1.5 miles to the north and a quick trip to the University of Indianapolis 1.5 miles to the south. Cruft Street Commons is located within overlapping neighborhood boundaries. One is the well-organized Garfield Park neighborhood adjacent to the city park full of amenities. And the other is Bean Creek — a community making great strides despite challenges as a low-income neighborhood.

On this uniquely mixed-use block between Shelby Street and I-65 and bordered by Cruft Street and Nelson Avenue, Big Car enjoys a rare opportunity to repurpose and build an equitable, inclusive pocket community that will serve as a sustainable and affordable catalystfor quality of life in the surrounding neighborhoods, the southside, and around the city — while avoiding displacement.

“We’ll secure long-term affordability for artists while supporting neighbors in staying to enjoy a socially cohesive block,” said Walker.

This happens, in part, by establishing bonds between new and existing neighbors. “What drives us from places is the lack of connection to others. It is in connection that we build safe, functional, cities,” psychologist Mindy Thompson Fullilove wrote in her 2013 book, Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities.

This idea directly addresses primary goals in the South Indianapolis (So Indy) Quality of Life Plan created by residents in eight southside neighborhoods, including Bean Creek and Garfield Park. Certified by the City in 2017, the plan is now in its implementation stage with staff and neighbors leading the way. Related So Indy goals include increasing mixed-use and quality rental housing, boosting job opportunities with an emphasis on trades, focusing on healthy food and gardens, increasing small businesses, and fostering social connectivity with affordable public programs.

“We’ve been closely involved in this from the start and serve as So Indy’s convener and umbrella organization. We’re very dedicated to supporting its work in the southside community,” Walker said. “And, together with So Indy, we’re dedicated to equitable and inclusive community development with thoughtful approaches to keeping existing neighbors involved and informed. And we’re working hard to avoid displacement while building an even more diverse and resilient community on the south side.”

Another key component of the Cruft Street Commons project is providing Indianapolis artists and owners of creative businesses a long-term home neighborhood they can afford — one directly owned by a nonprofit committed to keeping rent prices low for residential and studio space. After Fountain Square’s Wheeler Arts Community went market rate in 2017, Indianapolis no longer offered any affordable housing specifically for artists. And, due to market forces, artists and creative small businesses like galleries have moved from neighborhoods they once sparked with energy.

This cultural migration and disbursement not only makes things difficult for the artists; it also alters the authenticity, quirkiness, and cultural vibrancy of neighborhoods like Mass Ave and Fountain Square — the very kind of quality places that help Indianapolis retain young talent, a key issue according to studies by the IU Public Policy Institute. Data from its 2015 Thriving Communities Thriving State report shows that Indianapolis has been losing residents for 15 years, with 10,000 people leaving Marion County in 2015 alone.

Continuous displacement of those in the creative industry has the potential to increase the net out-migration. That’s why IU PPI emphasizes the importance of finding sustainable solutions to retaining talent. Several of the report’s suggested steps resonate with our strategies here. The report’s overarching recommendation for quality of place in Indianapolis: “Ensure adequate resources to preserve our heritage, develop amenities, and create unique places in a way that promotes a high quality of life.”

Building a place for artists and community

This multifaceted project is an expansion of Big Car’s existing work — also on the same block — that includes five affordable artist-owned homes as part of a community land trust developed as the Artist and Public Life Residency (APLR) in partnership with Riley Area Development and supported by INHP. Artists began to occupy APLR homes in 2019 with it expanding to 16 houses (some rented and some co-owned) by 2022.

Cruft Street Commons is linked directly with APLR as well as our program with two existing artist residency houses Big Car owns and manages separately on Cruft Street. These houses, currently occupied by short- and long-term artists in residence — border the green space that includes our community garden and chicken coops.

The greenspace is also home to the Indianapolis Bee Sanctuary, a public art and ecology project created by St. Louis artist Juan William Chávez and the Big Car team. Big Car has hosted several artists in its short-term residency program and four in our one-year residency program in these houses since 2016. And the two houses have both been utilized for exhibitions and other cultural programming — both inside the houses and in the greenspace.

As part of building common spaces for artists, neighbors, and visitors, Big Car is also renovating additional flexible programmatic and community space. This includes 20-25 flexible art studios at the 46,000-square-foot second former Tube Processing factory building along Nelson Avenue. This building is located directly behind our short-term residency houses and just southeast of Big Car’s existing community and cultural space, Tube Factory. In addition to these long-term affordable artist studios (something our city is lacking due to changes in neighborhoods like Fountain Square), Big Car plans to add exhibition space, a flex black-box performance and event area, culinary incubator space and cafe, community gathering space, and office space for creative/cultural nonprofits.

Cruft Street Commons residents will receive access to shared resources and performance space. Artists and nonprofits in the discounted studios and office space will also be involved as part of the team — along with Big Car staff artists and long-term residents in the affordable housing on the block — working in support of the community.

Polina Osherov, executive director and editor in chief of Pattern — a cultural and economic development nonprofit that works to retain talent and support creatives in Indianapolis and a partner as a potential tenant in the studio space — has been seeking a long-term home for 10 years. Pattern also conducted citywide research and determined a strong need for space for artists and entrepreneurs when it was launching a maker space.

“There’s huge pent-up demand for creative space in Indianapolis for artists,” Osherov said. “I have first-hand experience through surveys and talking with many many members of the community about the need for space. One of the challenges we face is financial. We don’t see more artists forming clusters of communities because they can’t afford it.”

Osherov sees ownership of Cruft Street Commons by a nonprofit as vital to long-term security for artists and organizations often pushed out of space. “The interests that developers have and the interests that a nonprofit organization like Big Car have are quite divergent. Big Car wants to support artists and keep them in place and allow them opportunities to grow and for the community to grow. Developers want to make money. So when the opportunity arises to make more, the artists fall by the wayside.”

Brian Payne, president and CEO of CICF, agrees that creating a sustainable home for artists is vital for Indianapolis and a crucial element of what draws CICF to Cruft Street Commons. “We’ve always been very aware that artist major catalysts for neighborhoods. And when neighborhoods make progress, artists get rushed out, get displaced. This project is a way for artists to stay in place and be part of a neighborhood for the long term and even build equity and personal financial stability.”

Drew Klacik, senior policy analyst with IU PPI — the evaluation partner on Cruft Street Commons — sees strength in keeping artists in place while also supporting existing residents. “Another really important element of this project is that intersection between art, artists, community and creating great neighborhood cohesion and sustainability,” he said. “One thing that makes this effort so interesting is how can we — with a combination of art, artists, and community — help everyone raise their level without actually driving folks out of the community. So the focus is on enabling a capacity building within the neighborhood — strengthening the neighborhood and its original residents.”

Artists in support of public life

As part of the program, Big Car will ask artist and community leader residents — all of whom receive discounted, below market-value housing, studios, and access to shared resources and spaces — to get involved as part of a bigger civilian service corps teaming up with community members to work as problem solvers and community connectors and builders for stronger social cohesion.

This structure for artists supporting the community, already part of our artist homeownership program, is now linked to a subsidized rent program. The civilian service corps exchange is something residents selected for the program formally agree to do.

“We’re confident the artist residents will want to do this and will consider it a key component to their practices. We’ll help ensure this by utilizing a selection process like the one for the first round of the homeownership program on Cruft Street. With this, we sought residents who consider community collaboration vital to their work. We know there’s interest in this idea as we had 66 artists reach out, 45 apply, and 14 complete the full process,” Walker said. “When we interviewed artists during the process, they told us that they didn’t view the requirement of giving back 16 hours to the community each month as a potential burden. In fact, they said that being part of this effort was a big part of what attracted them to the program.”

Building community through art

With the South Indianapolis Quality of Life Plan’s goals and broader societal and civic challenges in mind, Big Car is building Cruft Street Commons as a sort of micro cohousing community with arts-based social connectivity as its core mission. Cohousing communities are places found around the world where neighbors know each other, enjoy common spaces, and work together on shared goals.

“Functioning much like traditional villages, Cruft Street Commons will build on innovations from cohousing projects in the United States and Europe that we’ve studied,” Walker said. “We see cohousing — with its shared common spaces and regular opportunities for social interaction — as a powerful way to address how modern city design and changing lifestyles have led to isolation and a resulting decline in quality of life.”

As sociologist Robert Putnam shared in his 2000 book, Bowling Alone, almost half of Americans say they have no one, or just one person in whom they can confide. “Social isolation just may be the greatest environmental hazard of city living,” Charles Montgomery wrote in his 2013 book Happy City, an examination of the impact of social cohesion on happiness. “The more connected we are with family and community the less likely we are to experience colds, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, and depression.” He also shared that, if 10 percent of Americans had someone to count on in life, this would have a greater effect on national life satisfaction than giving everyone a 50 percent raise.

It is well worth noting that Indianapolis ranks 133rd of 186 cities in the 2017 Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index, the leading study of American happiness and health. “In response to the challenges caused by unhappiness and social disconnect in our home city, we’re building this pocket neighborhood to promote social cohesion for those who will live and work there, all neighbors, the broader community, and visitors from anywhere,” Walker said.

Cruft Street Commons fosters a sense of place, prioritize people over cars, and share resources like lawn mowers, appliances, and tools among artists in the program and other neighbors as well. Like other cohousing communities Big Car has studied, this will be a place where people care about each other and shared physical spaces — and support neighbors.

Regular community meals, shared workshop and gathering space, and community collaborations will help incubate ideas and form ongoing bonds and collaborations between artists living and working here. Cruft Street Commons will feature outdoor and indoor spaces where neighbors connect with each other spontaneously or at planned activities like shared meals at Tube Factory — already a central civic commons for the southside and broader community.

“Connecting neighbors through meals and other approaches to community engagement is crucial to quality of life and individual happiness. And we’ll start on our block and bring this kind of approach, with leadership from the community of artists, to neighborhoods across the south side and the entire city,” Walker said.

“People who say they feel that they ‘belong’ in their community are happier than those who do not,” Montgomery wrote in Happy City. “And people who trust their neighbors feel a greater sense of that belonging. And that sense of belonging is influenced by social contact. And casual encounters are just as important to belonging and trust as contact with family and close friends.”

Dan Buettner, author of the 2017 book The Blue Zones of Happiness, is an expert on places where people live long and happy lives. In the early 2000s, he began studying “Blue Zones,” areas of the world where a high percentage of people live to be more than 100 years old. His book, published in 2009, shares that a cornerstone of a long and healthy life is living in a happy, socially connected way. And he writes that communities can be retrofitted to encourage happiness and social cohesion. Combined with other factors, such as encouraging healthy eating and activities like walking and biking, Buettner believes creating mini “Blue Zones” is a realistic approach to boosting quality of life (and longevity) for people.

Buettner also shares that individual happiness is affected by how close members of social networks live to each other. When a friend who lives within a mile becomes happy, you are 25 percent more likely to become happy yourself as a result. But the happiness of a friend who lives further away has no impact — more support the strength of a micro-community like this one where neighbors bond over shared interest and purpose.

Orienting outward and bridging divides

Most cohousing and micro community projects are built with an internal focus on the people who live within the property boundaries. Cruft Street Commons will function as a more inclusive kind of community that is porous and invites all neighbors in — including those outside of the program — to develop deeper relationships and better know and support each other. This approach is something our research indicates is not happening in many other cohousing projects. “It’s an act of outward-looking leadership, a leadership that is concerned not only with the well-being of the institution itself, but also with the well-being of the greater community it seeks to serve and represent,” Rip Rapson, president of the Kresge Foundation, said of this kind of cultural development in a 2016 speech.

Strong connection between neighbors and artists at Tube Factory is already happening as Big Car staff artists are in constant communication and collaboration with nearby residents. Attendance at Tube Factory events is often more than 50 percent neighbors. And residents on the Cruft Street block participated in the selection of artists chosen for the home ownership community land trust.

“We’ll build on these relationships as we continue to bring new residents into this block that was half vacant for many years. Our programmatic focus for resident artists, in the foreseeable future, will be to work with neighbors and utilize cultural strategies to bring people together and form strong social bonds,” Walker said, noting that Big Car will accomplish this by facilitating and supporting public participation in what is called “informal arts” created together with the community. “That’s the kind of work we do all of the time.”

And Big Car teams up with community leaders, when invited into neighborhoods beyond our own, to support and program “third places” — like community centers, coffee shops, placemaking plazas in parks, etc. — where people can connect with others beyond home or work. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg wrote in his 1999 book The Great Good Place: “To comprehend the importance of the informal public life of our society is to become concerned for its future. The course of urban growth and development in the United States has been hostile to an informal public life; we are failing to provide either suitable or sufficient gathering places necessary for it. The grass roots of our democracy are correspondingly weaker than in the past, and our individual lives are not as rich.” One of the jobs of creating great third places is offering places for people and places for interaction, conversation, and learning between generations. “Third places provide a means for retired people to remain in contact with those still working and, in the best instances, for the oldest generation to associate with the youngest,” Oldenburg wrote.

People of all ages and backgrounds are hungry for opportunities to socialize with others. According to the National Endowment for the Arts 2015 study When Going Gets Tough: Barriers and Motivations Affecting Arts Attendance, 73 percent of people view socializing as their top motivation for attending arts programming.

In our data from Spark Monument Circle in 2015, we found that — far and away — the top attractor for people was being around other people. We also found that 85 percent of Spark visitors talked with someone they didn’t know — something 30 percent of them said they don’t usually do.

The Chicago Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College studied community theater groups, choirs, painters, quilters, musicians, writers, and others practicing art in informal settings and in collaborative ways in 22 Chicago communities to create its 2002 report: Informal Arts: Finding Cohesion, Capacity, and Other Cultural Benefits in Unexpected Places. These activities — the kind of work artists in this program will do — had these results: “over 80 percent of respondents to the survey indicated that making new friends was one of the significant benefits of interacting with diverse people in the course of art making. Close to 70 percent stated that they gained a greater understanding of different people.”

Bridging divides is central to the resilience of our society. Carol Colletta, a senior fellow with Kresge Foundation, is a co-founder of the Reimagining the Civic Commons five-year, $40 million initiative in Akron, Memphis, Detroit, Chicago, and Philadelphia. This program is reversing division by creating places for people to connect — could be formerly vacant lots or buildings, libraries, neglected parks. The approach, much like our own, is built around creating new centers for democratic activity, talking, and gathering. Colletta wrote in The Hill: “We strongly believe in the power of civic assets to break down barriers between citizens and to knit together communities. We need to gather together — differences and all — and start the conversations that will usher in a more unified future.”

And Big Car will turn talk into action with artists and neighbors in the lead addressing challenges. A 10-year study by the University of Michigan of-Flint, Michigan shows that neighbors making their streets “busy,” cleaning and beautifying abandoned properties, and turning some into programmed pocket parks led to drastic drops in crime — assaults decreased 54 percent, robberies 83 percent, and burglaries 76 percent between 2013 and 2018. This is the kind of work our crew of artists will help make possible — together with neighborhood leaders — on the southside of Indianapolis and around our city.

The power of partnerships

This is certainly a large and multi-faceted and challenging effort. But Big Car has taken steps toward owning and managing property and working with larger groups of artists. And it is teaming up with some of the city’s best experts in all aspects of this work. For instance, this is not an excessively large project for key partners including CICF, Deylen, Rundell Ernstberger, Blackline Architecture, and Indiana University Public Policy Institute. Leaders from each of those entities express full confidence in the project and in the team assembled to get it done.

“With CICF, we worked on the design of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail — clearly a transformational project. And we think this project — with the top-notch group of community partners Big Car has assembled — has the possibility of creating that kind of impact,” said Kevin Osburn, president and managing partner of REA, a multidisciplinary firm that will design the greenspace and streetscape. “What’s interesting is this combination of vision that comes from the creative side of the team as well as the experience and the seasoned experts at not only getting these types of projects off the ground but the detailed work of design and implementation and construction — and beyond that — management and sustaining of these types of projects.”

IU Public Policy Institute will lead the development and implementation of strong research design, complete necessary data analyses, and write and disseminate research findings over three years with the project and its programs. “We’ll be doing real-time evaluation of both process and outcomes and effort. So we will be able to intervene both when things are going well so we can maximize those opportunities and when things are going less well and we can intervene and help improve the process,” said Klacik of IU PPI. “We’ve done research for a long time that suggests that the status quo is actually a bad outcome. So supporting innovative ideas like this one becomes really essential in helping Indianapolis and all of the neighborhoods within it compete within the Midwest, across the nation and globally for talent and to increase opportunities to develop the latent talent within our community.”

The Learning Tree — an ongoing partner in multiple ways, including an INHP-funded home repair project and exhibit of neighborhood art on discarded doors — will facilitate connecting artists with inclusive community-driven work elsewhere around the city. The Learning Tree is a grassroots association of neighbors specializing in asset-based community development and education. “Knowing people and having connections starts with our biggest currency, which is trust,” said DeAmon Harges, founder of The Learning Tree.

The South Indianapolis Quality of Life Plan organization — which includes a paid full-time director, volunteer board, and representatives from eight neighborhoods and seven action teams (community building, connectivity, education and workforce, health and wellness, housing, Madison Avenue, and Shelby Street corridor) — will connect artists and leaders in Cruft Street Commons with projects and initiatives.

The University of Indianapolis is a key partner with So Indy QoL as its original convener — before handing this off to Big Car in 2017 (and now lead by Southeast Neighborhood Development or SEND). And UIndy will team up with us on Cruft Street Commons and expand partnerships like we have had with the Social Practice and Placemaking graduate program that utilized Tube Factory as a base of operations for classes, community interaction, and exhibitions.

Why Big Car, why now?

As a nonprofit arts organization and collective of artists and community leaders, Big Car Collaborative has worked for 15 years strengthening and supporting Indianapolis, its neighborhoods and its people through equity-focused, arts-based approaches.

“Our work is built on community engagement, co-creation, and collaboration with many citizens, artists, organizations, and entities. This focus of being part of solving problems as artists has been at the core of our mission all along,” Walker said.

Big Car began as neighbors and artists bringing creative energy to the mostly vacant Fountain Square commercial district in the early 2000s. In 2009 at the height of the recession, the organization received a Great Indy Neighborhoods Initiative (GINI) Imagine Big grant that connected its artists to eight neighborhoods as part of its Made for Each Other project. With this, Big Car followed its mission of bringing art to people and people to art by collaborating with neighbors in West Indy, the Near Eastside, Near Westside, Southeast, Martindale Brightwood, Lafayette Square, Binford area, and Crooked Creek.

From that time forward, working with people in communities on participatory art was at the heart of Big Car’s practice as artists. “It’s not an outreach program. It’s our art. And our mission then, as it is now, was to support people of all ages and backgrounds as a way to strengthen Indianapolis. This work was, is, and will always be what Big Car does,” Walker said. “Our mission statement says: we bring art to people and people to art, sparking creativity in lives to support communities. Our work emphasizes working as artists to reach people who lack access to creative experiences in their lives, people who are outside of connections to social capital, people who feel that art and community development efforts are for someone else. We work for everyone because we believe too few people experience the joy of creativity; cultural events should be for everybody, everywhere; and all people should get to imagine, make, and play. These central beliefs and our focus on reaching all people make Big Car unique in Indianapolis and around the world.”

While working on the Imagine Big project in Lafayette Square in 2010, Walker spotted an abandoned tire shop that seemed perfect for a cultural community center. With no up-front funding but with lots of volunteer support, Big Car’s artists and volunteers transformed this eyesore into a 12,000 square-foot hub called Service Center for Culture and Community with a massive raised-bed community garden that doubled as a park where people could gather in front of Lafayette Square Mall.

In 2015, Big Car worked with the City of Indianapolis — with $400,000 in funding from the NEA, the City, and CICF — to spark Monument Circle with daily, human-scale activity and comfort while testing plans for the Circle’s redesign. And, now, we’re in the midst of supporting a neglected block in the Garfield Park neighborhood where we first began work with a collaborative gateway mural as a gift to the community in 2012.

Big Car’s idea for Cruft Street Commons grew out of much experience, from years of talking with neighbors, attending community meetings, creating neighborhood logos with fourth graders, digging sweet potatoes out of the dirt next door to Don’s Guns, painting creative crosswalks, taking boards off windows of buildings vacant for 15 years, and helping give voice to people across the city who’ve been left out for too long.

“This idea comes from years of research, reading dozens of books and articles and bringing artists and leaders to Indianapolis to share their work with the community. We’ve also travelled to visit sites and speak with colleagues about their work — asking many questions and learning much — from Project Row Houses in Houston to Heidelberg Project in Detroit to Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago to the Mattress Factory museum in Pittsburgh,” Walker said. “Our idea for strengthening Indianapolis through arts and cultural innovation grew thoughtfully and carefully from giving much of our lives and all of our hearts to this challenging, messy, beautiful, rewarding, and vital work.”

Reading list:

- Buettner, Dan. The Blue Zones of Happiness: Lessons From the World’s Happiest People. National Geographic, Washington D.C. 2017.

- Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities. New Village Press. 2014.

- Helliwell, John. “Trust and Well-Being.” International Journal of Wellbeing, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 42-78. 2010.

- Indiana University Public Policy Institute. Thriving Communities Thriving State. Indiana University Press. 2015.

- Klineberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. Crown, New York. 2018.

- Mollison, Bill. Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual. Tagari Publications, Tyalgum, Australia. 1988.

- Montgomery, Charles. Happy City: Transforming our Lives through Urban Design. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2013.

- National Endowment for the Arts. When Going Gets Tough: Barriers and Motivations Affecting Arts Attendance. NEA Research Report #59, January 2015.

- Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA. 1991.

- Putnam, Robert. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000.

- Solomon, Daniel. Housing and the City, Love Versus Hope. Schiffer Publishing, Atglen PA. 2018.

- Wali, Alaka. Informal Arts: Finding Cohesion, Capacity and Other Cultural Benefits

in Unexpected Places. Chicago Center for Arts Policy at Columbia College, June 2002.

‘

‘